NOSTALGIA: a wistful or excessively sentimental yearning for return to or of some past period or irrecoverable condition

– Merriam-Webster

Millennials are often accused of being obsessed with childhood nostalgia. But for me, childhood isn’t something to long for—it’s something I survived. Growing up in a far-flung Brooklyn housing project in the early 1990s, I qualified for reduced-cost lunch at school, and my family relied on food stamps and WIC checks. As white residents in a majority-minority neighborhood, we were outsiders in more ways than one, and I stuck out like a sore thumb among my black classmates. To outsiders, the Brooklyn of the era was a scary place, the setting of countless rap songs and crime movies. Both my parents worked constantly, and they frankly had neither the time nor the will to supervise me, in stark contrast to many of my peers who recall growing up with “helicopter parents.” I was a solitary child who spent most of her time reading or watching television.

My family didn’t have cable, so the only children’s programming available to me were PBS Kids and Saturday morning cartoons. By the time I was seven, I was still watching childhood favorites such as Sesame Street and Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, but my palate had already expanded to include shows designed exclusively for adult consumption—gritty dramas like NYPD Blue and, of course, Beverly Hills, 90210.

Early in life, I was drawn to characters with an edge: first, Oscar the Grouch, then Married… with Children’s Peggy Bundy. To me, there was no hard line between children’s programming and “all that other stuff.” If it was on TV, I watched it. By the time I was five, that meant stumbling upon Beverly Hills, 90210, first catching up on the high school years during daytime syndication. It didn’t take long for me to become a hardcore fan, and I devoured the show with a hunger normally reserved for Barbie dolls or a Sherlock Holmes mystery (I read those stories at that age as well).

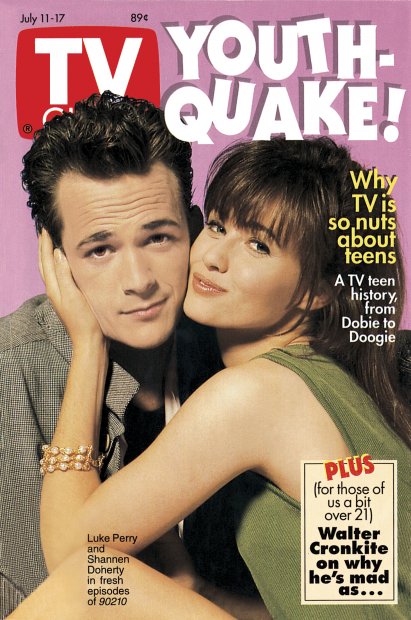

90210 was undeniably my first favorite television program, but I kept my obsession with it largely a secret. No one on the playground talked about Brandon and Kelly’s on-again, off-again drama, and I knew better than to bring it up. The show was too mature, too sexual, too “grown-up”— far too inappropriate for my peers, whose parents were apparently more discerning than mine. I knew even back then that my media diet wasn’t normal, that the glossy, drama-filled exploits of Brandon, Dylan, Kelly, Donna, and the others weren’t designed for a kid in single digits living in a Brooklyn housing project. But that didn’t stop me from absorbing it.

The neon-drenched opening credits and impossibly good-looking cast hypnotized me, providing a window into a life beyond my comprehension. These people had mansions, cars, and closets full of outfits that changed every episode. Their lifestyle was foreign to me and their problems—breakups, betrayals, and implausibly complex social hierarchies—were a world away from mine, but I watched them with the same intensity as if I were studying for a spelling test. I wanted so badly to be a “California girl.”

At my early age, I didn’t fully grasp what was happening on screen, but I understood that Beverly Hills, 90210 was about things that were supposed to be important to adults: romance, sex, rebellion, social status. I kept track of every breakup, every betrayal. I knew Dylan McKay was the kind of bad boy older girls fell for—he was my favorite character by far, less so because he was brooding and more because, even then, I could tell Luke Perry was the best actor on the show. The relationships on the show were dramatic, full of teary breakups and passionate makeups—concepts I had no real-world context for, but I filed them away for later, assuming that’s what being a young adult was supposed to look like.

The sex, in particular, went over my head. Even at seven, I could tell sex was everywhere—woven into the dialogue, in the kisses that lingered too long, in the way the camera panned away just before something “bad” happened. I didn’t fully understand what Donna was holding out on or why David was so impatient, but I knew it mattered. I remember sensing the weight of when Brenda lost her virginity to Dylan, even if I couldn’t put it into words. It was the kind of thing that made adults mad and made kids feel like they were learning a secret they weren’t supposed to know.

Looking back, I can’t precisely pinpoint how Beverly Hills, 90210 shaped me, only that it must have. Maybe it planted the first seeds of class consciousness, or maybe it just confirmed what I already knew: that some lives were easier, more privileged, sun-drenched, and dripping in excess. I envied those lives, but the real hook wasn’t the money—it was the longing, the search for belonging. Maybe that’s why I devoured every episode. In its own strange way, 90210 wasn’t just an escape—it was also a window into a world I couldn’t completely understand, but that I aspired to be a part of.